IF ANY ONE characteristic could define PLF, it would be our perseverance. Our unwavering belief in the Constitution, and the individual liberty it protects, steels us even when we face the longest odds. When we defended the Sacketts’ right to challenge outrageous government threats and bullying, it did not matter that every court had denied similar property owners their day in court. We knew that justice would win out. We were rewarded for our stubborn belief in the Constitution with a unanimous Supreme Court victory in 2012.

Our optimism remains just as unshakable today as we ask the Supreme Court to take up another issue that PLF has been working on for decades. In September, we petitioned the Supreme Court to hear our client’s challenge to a federal regulation that exceeds Congress’ enumerated powers. For decades, we have been fighting federal overreach under the Constitution’s Commerce Clause. Now, the Supreme Court has an opportunity to restore the Constitution’s limits on federal power and dramatically shrink the administrative state.

A federal regulation forbids the people of southwestern Utah from doing things that most of us take for granted in our own communities, ostensibly to protect the Utah prairie dog. The regulation is so extreme that it makes it a federal crime for state biologists to move prairie dogs from backyards, parks, and the airport to public conservation areas that have been set aside for the species’ permanent protection. Greg Sheehan, the former director of Utah’s wildlife agency and now principal deputy director of the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, aptly described the situation as “a quagmire of federal bureaucracy.”

That quagmire is both unconstitutional and counterproductive. The Utah prairie dog regulation is not the regulation of commerce. There is no market for Utah prairie dogs, nor any economic activity involving the species. If this regulation is constitutional, there are no remaining limits on federal power.

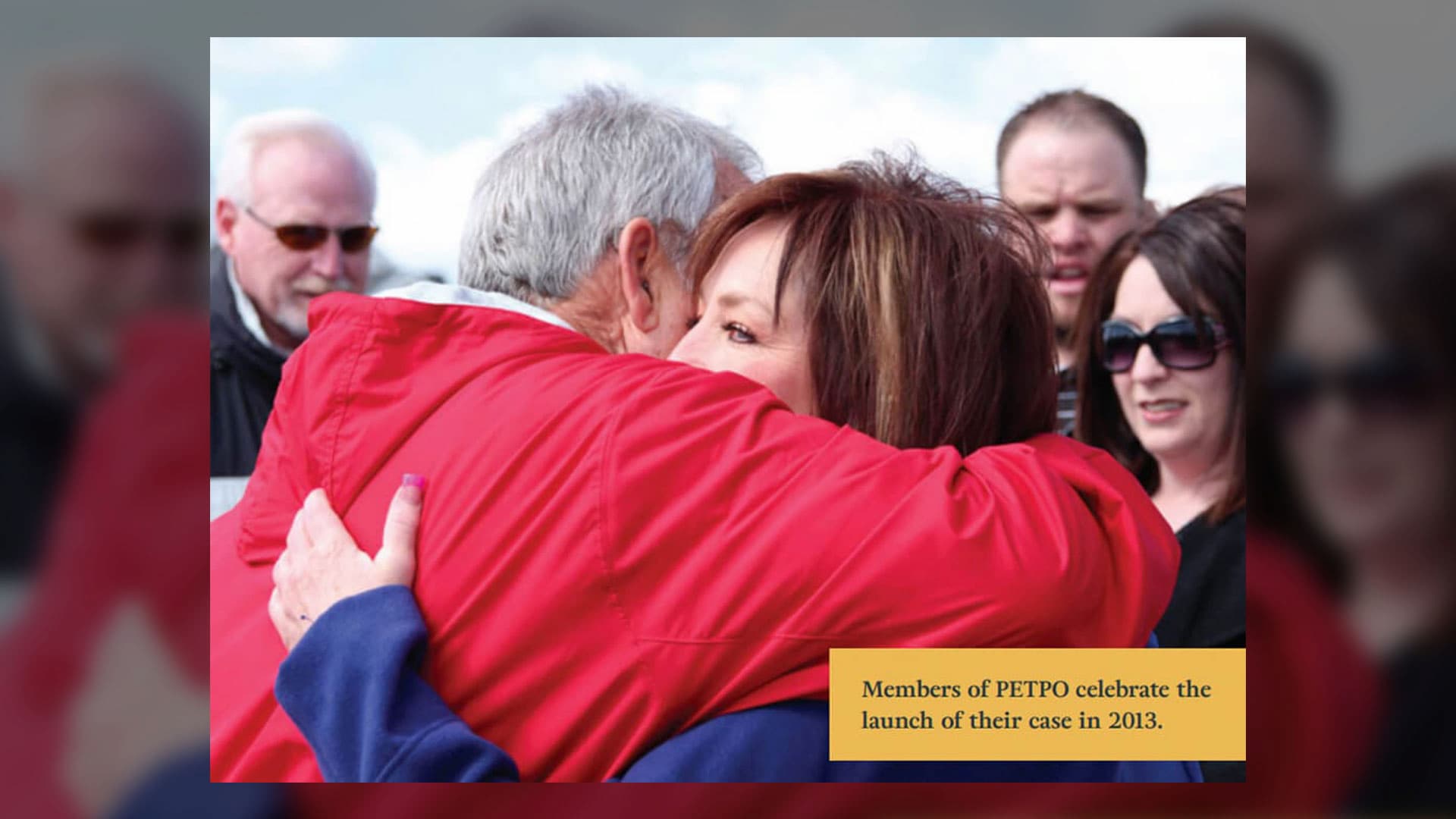

The regulation is also counterproductive. “Decades of federal regulation have created a lot of conflict but haven’t brought us any closer to a long-term plan to protect the Utah prairie dog,” said Derek Morton, spokesman for People for the Ethical Treatment of Property Owners, our client in the case. That changed in 2015, when a federal court struck down the regulation as unconstitutional and returned management authority to the state. Since then, Utah has improved habitat on state lands and state biologists have partnered with property owners to move prairie dogs from developed areas to state conservation lands.

The Utah prairie dog population has thrived under state management, with recent population estimates more than double what they were just seven years ago. Unfortunately, the Tenth U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals restored the federal regulation this summer in a decision that defied any limit on federal power.

So the fight to recover the Utah prairie dog and restore constitutional limits on federal power continues. If the Supreme Court agrees to hear the case, which we should learn in January, our perseverance will have paid off once again.