THE FIRST ROUND of nerves really bubbled up when I finally made it to Philmont’s base camp. I’d been to Boy Scout camps and countless campouts before but this was the big one: This was Philmont. No amount of merit badges on a khaki uniform could prepare me for those visceral feelings of uncertainty, awe, and excitement for the adventure I was about to experience.

Amazing plots of wilderness do that—they exhilarate you to be part of something so closely linked with the natural world.

Philmont is a 140,000-acre ranch owned by the Boy Scouts of America in northern New Mexico near the Rocky Mountains. More than one million young men have hiked the trails there and it stands as the pinnacle of everything scouting has to offer adventure-loving youth. The reservation is also one of the largest privately owned and administered conservation projects in the world.

But this isn’t a questionably placed promotion for a Boy Scout camp in the middle of a magazine on coastal property rights. This is an illustration of how vital privately owned conservation projects, and the property rights that make them possible, are for champions of nature—and liberty.

When guided along the trails of Philmont you learn a lot about the land, the history of the region, and the stewards who have lived, worked, and ranched there over the last 90 years. You also learn that Philmont is in a healthy competition for the crown of largest private conservationist of the West.

Next door to Philmont is the Vermejo Park Ranch, owned by the media magnate Ted Turner. He is coincidentally also one of the largest private landowners in the world, with more than two million acres across the country, nearly all of it undeveloped and reserved solely for environmental projects.

The Boy Scouts of America is a protagonist you’d expect in a story of conservation champions; a billionaire media mogul is more of a stretch. But that’s what strong property rights can produce: A system where anyone can contribute to the fair and sustainable protection of America’s beauty.

The ranch manager of another one of Ted Turner’s properties, the Flying D Ranch, shared an anecdote in The Land Report magazine that gets to the heart of why so many of us fight for conservation with property rights:

When Turner learned that South Dakota’s Standing Butte Ranch was going to auction and about to be divided up, he preserved the pristine prairie by buying it outright.

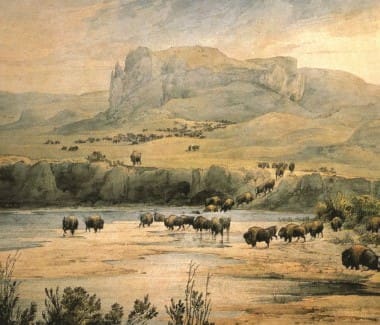

Then Ted said to Bud and me, “You see this watercolor?” It was a painting of bison crashing through the underbrush in Northern Montana. He said, “That’s what I want the Flying D to look like. Those Angus cattle? Gone. Those tractors putting up hay? Gone. Those power lines? Gone. That’s your job, boys. And what do you know about bison?”

“Not much” Was the answer. Well, you better start learning because that’s what we’re going to be running.

The Flying D is a working ranch serving as a habitat for bison, deer, elk, moose, and myriad other endangered and threatened animals. It’s the exact vision of what Turner wanted for the property.

The opportunity to make a piece of nature better through ownership is how we can live up to our responsibilities as stewards of our plot of earth. I know now that’s part of the connection I was feeling as a 15-year-old Scout. I was honoring the purpose that the Boy Scouts have for their land and I was carrying out the vision Waite Phillips—the oil tycoon—created when he donated Philmont’s land to the Scouts so long ago.

It’s a coincidence that Philmont and Turner’s lands sit next to each other. But the fact that two of the largest and most successful conservation projects in the Southwest are privately owned is no accident. The Framers knew what too many of our leaders today are still learning: Individuals care for what they own better than the government controls what it takes.

Turner might not have been thinking about how he was exercising his property rights when he envisioned herds of bison powerfully lumbering across his ranches; I know land policy was the farthest thing from my young mind sitting there at base camp. But perhaps that’s how it should be. The great American experiment is made possible by our fundamental ability to freely build on, preserve, or live on our land. We don’t always think about that fact until it’s threatened. Honor that freedom by experiencing firsthand the beauty that it makes possible.