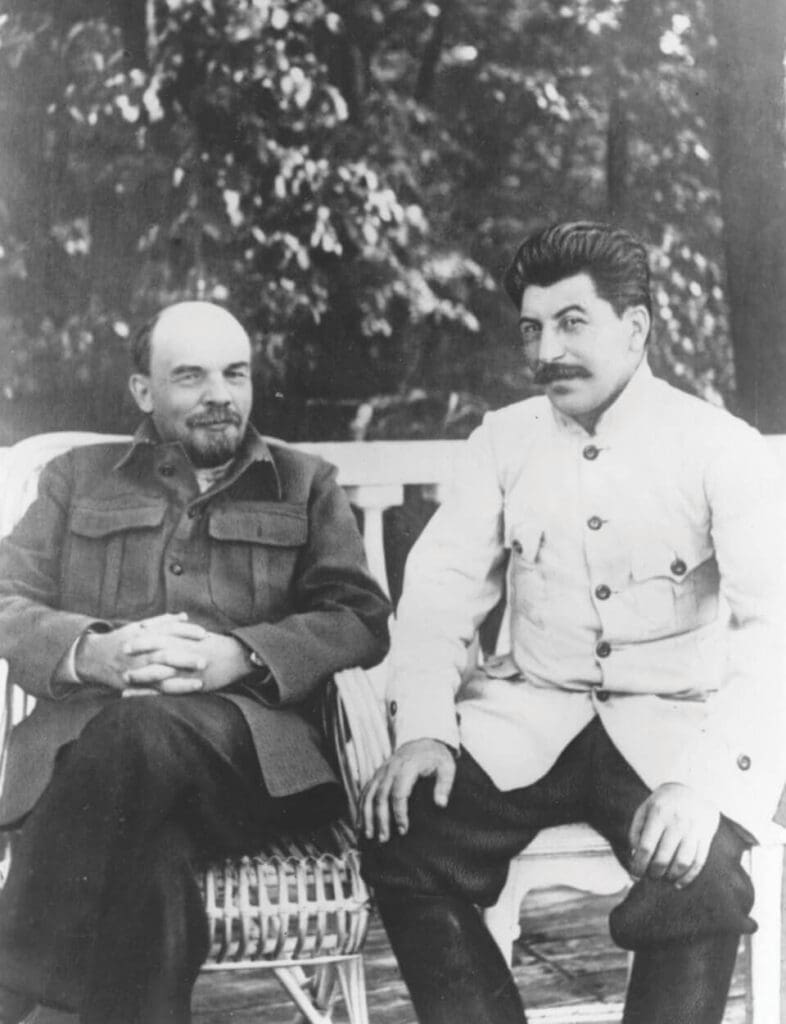

IN 1917, VLADIMIR LENIN—the Russian revolutionary who led an overthrow of the Russian government—was trying to hold his country together.

The Revolution had decimated the motherland’s roads and railways. Russia lacked consistent power sources, and food shortages were frequent. Most of Russia’s skilled workers had fled, so the majority of the remaining people were impoverished, uneducated, and unskilled peasants.

Fortunately, Lenin had a solution for Russia’s foundering economy and infrastructure: a new business and academic concept called managerialism.

Frederick Winslow Taylor, a U.S. business consultant who developed the concepts of managerialism, could never have predicted how his ideas would lead to the atrocities of the Soviet Union. But managerialism and socialism were natural dovetails to each other. After the Revolution, Lenin wrote, “We have won Russia from the rich for the poor, from the exploiters of the working people. Now we must manage Russia.”

By the early 1920s, Russia had at least 10 managerial studies institutes, 20 managerial journals, and a bureau of managerial studies. As Judith Merkle points out in her book Management and Ideology, both Marxism and managerialism had a “vein of latent pseudoscientism.” Both advocated for a society managed from the top down by experts.

This sociopolitical experiment with managerialism and socialism was exciting for Lenin, his successor Stalin, and the leaders of the Communist Party. But it was equally—if not more—exciting for another group too. American progressives were reveling in what the Soviet system could mean for their dreams of scientific rule. And a group of progressive academics were planning a Russian junket to try to make their dreams a reality in the U.S.

THE AMERICANS ORGANIZED their junket in 1927, before the destruction and body count of the Soviet regime had reached its hellish peak. They were academics, journalists, and union leaders. They were (by and large) not Communists, but they did share the progressive distaste for markets and individualism. They wanted to see this new Soviet approach to the economy in action. How did they build their cities? How did they run their factories and farms? Could a centrally planned economy work?

The junket hoped this radical new national experiment would inspire new ideas that they could take back to the United States.

Among the group were Rexford Tugwell and Stuart Chase. Tugwell was an experimental economist at Columbia University. Peers considered him charming. One likened him to a “cocktail” that “made your brain race along.”

Tugwell was raised in a farming family, and although he grew up well-off relative to his neighbors, he saw first-hand how rough the boom-and-bust cycles of farming could be.

During the junket, Tugwell was interested in seeing if the Soviet government’s centralized farming policies could prevent the economic busts he knew so well from his youth. Top-down management of complex systems already appealed to Tugwell, who was a fan of Taylor’s managerialism and its potential for American society writ large. Tugwell called Frederick Winslow Taylor’s pig iron study the “greatest economic event of the 19th century.” And he had long been interested in radically reforming how government worked. In a college periodical, Tugwell published a few lines of idealistic poetry: “I shall roll up my sleeves—make America over.”

Chase, an accountant-turned-social-theorist, was also an idealist who was quite hostile to free market economics. Chase was a fan of Taylor’s ideas as well, especially his application of engineering concepts onto society. Author Amity Shlaes sums up Chase’s worldview as: “Engineers were good, consumers were good, businessmen were suspect.”

Chase had read with horror about tragedies in American sweatshops and believed that unless the government took a strong hand, factories would never improve working conditions. He would later describe an ideal socialist state managed by “those who understand the machine: engineers, scientists, machinists, foremen.” He felt that engineers were “the modern Prometheus in chains.” And here was the Soviet Union, implementing a planned economy designed by experts trained in Taylor’s ideas. Chase was interested in how it worked.

Most countries, including the United States, didn’t recognize the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics (USSR) diplomatically yet. But the Soviet Union drew international attention for undertaking what progressive activist Jane Addams called “the greatest social experiment in history.”

Chase and Tugwell wanted to know whether the Russian experiment meant America could move away from capitalism and toward collectivism and central planning. They hoped the Soviet Union would prove it could work. Chase, in particular, was convinced that Soviet Russia was the future: “Russia, I am convinced, will solve for all practical purposes the economic problem.”

The Americans in the junket were looking for innovative ideas, but Stalin had his own goals. He wanted to impress the American labor leaders in attendance and spread support for communism in the U.S. The more pressing issue, however, was that he needed money. Although the worst was still to come, the early Soviet economy was already failing. Impressing these intellectuals and labor leaders could help legitimize the Soviet Union and create diplomatic ties. Diplomatic ties could get them much-needed Western money.

FORTUNATELY FOR STALIN, the Americans liked what they saw. Tugwell was impressed with the centrally planned wheat farms. In particular, he admired agronom, the government bureau of farm managers which oversaw the country’s farmland. Unlike in the U.S., farmers would not be helplessly subjected to radical price fluctuations, the kind that had left many of his neighbors destitute when he was a child. He wrote, “With us, prices are a result; in Russia they are the agents of social purpose.”

Under the agronom, farming was a communal effort. This suited Tugwell, who saw competition and private ownership as wasteful. Expert management was rational, scientific, and efficient. In reality, the agronom system would turn out to be more efficient at starving people than at moderating price swings. But Tugwell believed he was seeing the future of American farming. He would later write, “I knew from then on how determined dictators come to manage a people.”

Stuart Chase was fascinated with Gosplan, the state planning commission. It was tasked with managing the entire Russian Soviet economy through economic expertise. Chase was awed, citing their bold “attempt to do away with wastes and frictions that do dreadful damage” in capitalist societies. Rational state planning of the economy was exactly what Chase believed the U.S. needed.

About Chase, Amity Shlaes relates how “the scale of the management took his breath away.” Chase fawned over Gosplan’s economic experts, and how they were “laying down the industrial future of 146 million people and of one-sixth of the land area of the world for fifteen years…. These sixteen men salt down the whole economic life of 146 million people for a year in advance as calmly as a Gloucester man salts down his fish.”

As the entire junket was marveling at the wonders of the Soviet’s planning systems, they began to know in their hearts that this was the future of society. However, what no one on the junket knew—not even Chase or Tugwell—was that Stalin carefully planned their entire trip, virtually every factory and farm, in advance. Every sight the Americans saw was staged for them like a perfectly scripted play. The junket saw much of Russia, but only the Russia Stalin wanted them to see.

They returned to the states on a ship (fittingly) called the Leviathan.

IN THE YEARS following the junket, Stalin intensified Soviet central planning. His first Five-Year Plan, which set long-term national quotas for industrial and agricultural output, was designed in part by a Russian-American (and Taylor disciple), Walter Polakov. In designing the Five-Year Plan, Polakov implemented principles of managerialism: charts, measurements, and, most importantly, quotas.

On paper, the results of Stalin’s Five-Year Plan were impressive. Consumer goods increased by 87%. Coal production nearly doubled, and iron ore output nearly quadrupled. Pig iron, the inspiration for Taylor’s theory of managerialism, increased two-fold in annual production.

But the impressive stats didn’t capture the true, unseen costs of the boosts in industrial output. The Five-Year Plan forced rural peasants off their land and into city factories. Then the state took control of all Russian farmland for “scientific,” “efficient” central planning.

Peasant property owners, or kulaks, were deemed enemies of the Revolution and Stalin declared that they should be “liquidated.” The Soviet secret police were instructed to shoot or imprison anyone who resisted collectivization or the seizure of grains. Through propaganda, the Soviets encouraged poorer peasants to turn against anyone deemed a kulak (the definition of a kulak quickly turned vague and was applied conveniently). Even children were instructed to inform on their parents if they resisted the collectivization of property. Those who did so were praised.

A culture of paranoia and widespread arrest ensued. The mass imprisonment was as much about maintaining authoritarian control as it was about hitting the industrial quotas. Millions of people were forced into gulags, brutal prison work camps. The laborers lived on starvation-level rations and worked on massive industrial and public works projects in subzero temperatures with minimal clothing.

This “free” labor helped the government reach or surpass some of the quotas of the Five-Year Plan. But it all came at a staggering cost. Centralizing agriculture and mass imprisonments were an enormous disruption of the food supply. The cities required more food because so many people were forced into factory work. Meanwhile, farmers were forced, at gunpoint if needed, to send their harvests to feed the industrial cities while they themselves starved.

Starvation and death became commonplace by the early 1930s. Ukraine, once known as the “breadbasket of Europe,” was hit particularly hard. British historian Robert Conquest, specializing in the Soviet Union, estimated that between widespread famine, mass executions, and disease, as many as five million people died during the first Five-Year Plan.

Many of those deaths were the direct result of attempting to centrally plan agriculture through collectivized farms. But many deaths were also intentionally inflicted. Some Ukrainian villages and towns resisted the Soviet ransacking of their land, crops, animals, and homes. Stalin “blacklisted” them, blocking them from receiving any food and essentially sentencing them to death.

Yet despite all the widespread suffering and death occurring because of their policies, Soviet leaders dismissed the millions dead, not as an avoidable tragedy, but as a benefit. In their eyes, they had eliminated dangerous “anti-Soviet elements” from the population.

WALTER POLAKOV RETURNED to the United States in 1931. He remained convinced the Soviets were successfully implementing managerialism. He joined a new consulting firm called Technocracy Inc., which advocated for a planned economy managed by engineers. He went on to consult for the Tennessee Valley Authority, one of the signature initiatives of Franklin Roosevelt’s first term in the White House. It was hailed by many as a promising first step toward nationalizing energy production.

After returning from his trip to Russia, Stuart Chase wrote extensively about what he saw, hoping to influence political leaders in the U.S. He argued that free market capitalism was a relic of a backward past, ill fit for the complexities of modern times. The economy of the future was collectivized, like Russia was. In 1932, he published a book praising the work of Frederick Winslow Taylor and advocating for government to “control from the top.”

Government, he believed, should be a dictatorship of scientists. He titled it A New Deal.

That same year, Rexford Tugwell joined Louis Brandeis as members of FDR’s informal team of advisers that he called his “Brain Trust.” There, Tugwell advocated for a “managed society,” with national planning of agriculture and industry.

Soviet propaganda poster which reads “Under the leadership of great Stalin—forward to communism!”

Both Chase and Tugwell believed that what they saw in Russia could bring the United States out of the Great Depression.

Some journalists, like Welsh reporter Gareth Jones, wrote truthfully about what they had seen in Russia and Ukraine. But even with starvation, death, and cannibalism in plain sight, Communist denial was strong. Jones wrote about a harrowing train encounter he had: “[A] Communist denied to me that there was a famine. I flung a crust of bread which I had been eating from my own supply into a spittoon. A peasant fellow-passenger fished it out and ravenously ate it. I threw an orange peel into the spittoon and the peasant again grabbed it and devoured it. The Communist subsided.”

Editors in America and Europe were in denial as well. The idea that a government would intentionally starve millions of its own citizens strained their credulity. Worse, many journalists actively lied about the brutality of Stalin’s regime. A New York Times reporter named Walter Duranty, who won a Pulitzer Prize in 1932 for his coverage of the famine, totally denied that there was any starvation. In a 1933 article, he acknowledged that the situation in the Soviet Union was bad, but “to put it brutally, you can’t make an omelet without breaking eggs.”

The New York Times eventually discredited Duranty’s reporting, yet the Pulitzer board has repeatedly chosen to let his award stand. Evidence has since proven that Duranty knew about the mass starvation as he was reporting about Russia’s prosperity. He chose to paper over the millions of deaths at the hands of the Soviets to perpetuate lies about the success of managerialism and the Russian system.

BY THE TIME the atrocities of the Soviet Union were apparent—and unavoidable—to the world, FDR’s New Deal was fully implemented in the U.S. Yet, despite a body count in the millions, the incredible failure of government centralized planning in the USSR did little to deter its champions in the West.

While the centralized planning of the New Deal was nowhere near as destructive as it was in the Soviet Union, many economists and historians, including Burt Folsom, Robert Murphy, Steve Horwitz, Harold Cole, and Lee Ohanian, argue that the New Deal prolonged the Great Depression by many years, created massive food shortages, and cost countless jobs when Americans were desperate for work—any work.

Collectivism, aided by Taylor’s cult of managerialism, created millions of Russian corpses.

The death and destruction that collectivism brought to Russia was the result of thousands of true-believers (from Lenin and Stalin all the way down to the government agency bureaucrats) willing to sacrifice the lives of their countrymen for their dream of a government-run utopia.

The transportation of many of those collectivist principles—powered by managerialism—from Russia to the U.S. was the result of a dedicated group of progressives who sailed to Russia to revel in its lies.