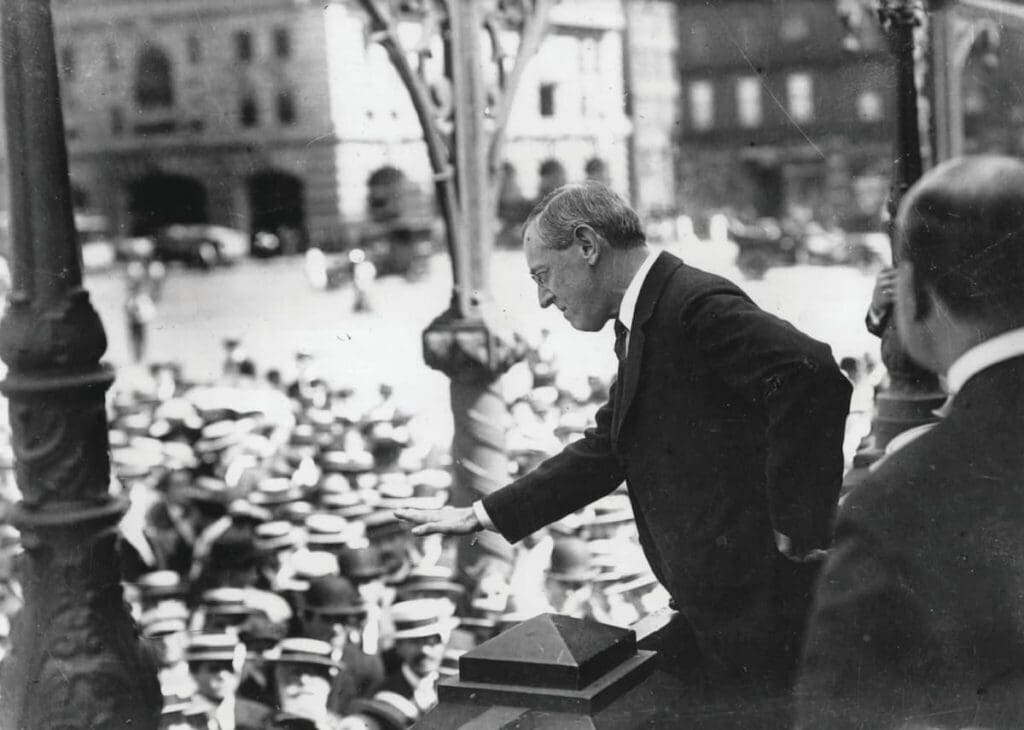

WOODROW WILSON SPENT most of his life in academia penning books about public administration. Even sympathetic biographers note Wilson’s prickly demeanor and tendency to think of himself as the smartest guy in the room. As author Robert W. Merry describes him, “His greatest flaw was his sanctimonious nature, more stark and distilled than that of any other president… He thought he always knew best, because he thought he knew more than anybody else.”

Before Wilson entered politics, he was an academic who lectured fiercely on the need for a strong centralized government. He was an early theorist of “public administration,” an emerging field that argued government should be a professional career.

Wilson, and many progressives of his era, were enthusiastic about the idea of disinterested experts, insulated from political partisanship, who seek to make government more efficient and more capable of providing for the people. Wilson believed government should go beyond “the protection of life, liberty, and property.” Instead, it should “serve every convenience of society.” What that looked like in reality was expanding how much of people’s everyday lives government controlled—or what progressives called “social control.”

Even though Wilson’s political views were similar to those of many other early-20th-century academics, his ambitions put him on another playing field entirely. Wilson would ascend to the top of the academic field, to the governor’s mansion in New Jersey, and eventually to the White House.

And once Wilson was the leader of the free world, he got to work on his life’s mission of transforming and expanding government into what he thought it should be.

HISTORIAN THOMAS LEONARD classifies Wilson’s philosophy as “quintessentially progressive.” Wilson thought experts “do not merely serve the public interest but lead the public interest by their superior ability to identify the social good.”

For the Founders, the public interest was in protecting our rights. For progressives like Wilson, it was about serving the collective: individual needs and desires should be subordinate to the state, for the benefit of all. Government expertise would be the tool by which progressives would identify and serve this public interest.

Wilson’s mission to transform government into one ruled by experts would be a Herculean feat requiring massive logistical, social, bureaucratic, and political changes. Changes not easily accomplished in Washington.

But it wasn’t politics holding Wilson back, it was the Constitution.

Wilson despised the Constitution. He, like most progressives, believed government was a living organism, not something that could be limited by simplistic checks and balances. In one of his books, Wilson wrote, “[Government] is accountable to Darwin, not to Newton. It is modified by its environment… Living political constitutions must be Darwinian in structure and practice.” The contemporary progressive push for a “living constitution” came right from Wilson’s writing.

“Society as a living organism” was a common analogy for progressives of the era. Author Thomas Leonard explains its implication: “If society really was a person—possessing a mind, interests, and a conscience—then the problem of determining what 75 million people wanted was vastly simplified. When actual individuals were deemed organs or cells, they were made subordinate to the social whole.”

Under Wilson’s model, the people formed the body, and an administrative state run by experts would be both its mind and its conscience. And because Wilson believed that society was “Darwinian” (i.e., alive and evolving), government could not be bound by some antiquated set of unscientific rules.

For Wilson, government could not survive if the different parts of its body were working against each other: “No living thing can have its organs offset against each other as checks, and live.”

FOUNDING FATHER JAMES MADISON, in Federalist Papers 51, wrote of the need for government power to be divided. If power becomes centralized, those with power would enrich themselves at the expense of the masses. Madison believed that the separation of power would ensure that each branch of government would prevent the other two from gaining too much authority: “Ambition must be made to counteract ambition.”

But divided power was a problem for Wilson’s dream of administration by experts, which required concentrated and unchecked power in the name of efficiency. Efficiency has many benefits, but it is always contextual. A more efficient assembly line drove down the cost of Henry Ford’s cars. But most of the world’s dictators have found efficient methods to dominate or exterminate their enemies.

On the campaign trail, Wilson gave rousing speeches about the importance of states’ rights. But he also told audiences that the federal government should be liberated from this antiquated system of checks and balances. Congress needed to be neutralized, and government power should be centralized in specialized executive agencies administered by experts.

Such experts could then, as Wilson wrote, “serve every convenience of society.” And by “serve,” he meant “lead.” Wilson wanted a government that controlled everything. The Founders wanted just the opposite. They believed in, and fought fiercely for, individual liberty. An all-controlling state would spell the end of that liberty—whether or not the people in charge are experts.

ONCE WILSON WON the presidency, he began constructing his administrative state. But even though public administration was his expertise, actually implementing the ideas was an enormously complex task. He needed help.

Wilson turned to his good friend and confidant, Louis Brandeis.

The first step in centralizing power in the executive branch was to bring money and credit under its control. The Federal Reserve Act was one of the first laws Wilson signed after he was sworn in as president in 1913. Wilson and his peers in Congress turned to Brandeis to help draft the act.

Historian Thomas McCraw described Brandeis’ role as taking two forms, “First, he advised the president on the degree to which private and public management could be mixed within the new Federal Reserve System; second, he took up his pen. The result was [the book] Other People’s Money and How the Bankers Use It.”

Brandeis’ book Other People’s Money proved to be influential in drawing public support for the Federal Reserve Act. Brandeis railed against large banks and trusts as inefficient and anti-competitive. He believed bankers had accrued far too much power over the economy, which a Federal Reserve System could address.

Brandeis’ worry over the curse of bigness wasn’t limited to the private sector. Government could become too big to be effective. Brandeis argued for a Federal Reserve that was decentralized but with some public control. And thanks in part to his influence with Wilson, he got it.

Brandeis also helped write the law that would form the Federal Trade Commission, which Wilson signed into law in 1914. The FTC was designed to protect businesses, through a national regulatory body, from too much competition. We are used to such an idea today. But at the time, it was an ambitious expansion of federal power over the economy.

While the FTC’s power was far-reaching, the establishing documents forming it were purposefully vague. Political scientist John Adams Wettergreen called the Federal Trade Commission Act “one of the poorest pieces of legislation ever written. [Never before had] Congress deliberately created agencies with broad, vaguely defined purpose and purview.”

By making the FTC’s powers broad but vague, Wilson and Brandeis succeeded in creating a massive government agency where “experts” controlled not only how their work got done, but what their work should be and how much power they should have.

Wilson’s vision of an expert-run administrative state was coming to fruition.

WHILE BRANDEIS REMAINED a behind-the-scenes influencer in Wilson’s administration, he never formally served in it. But when there was an opening on the Supreme Court, Brandeis immediately was on Wilson’s short list. In 1916, Wilson appointed Brandeis to the High Court, where he would join Oliver Wendell Holmes on the bench. Holmes was popular with progressives for his arguments in favor of restricting economic liberty.

Brandeis’ appointment ensured that progressive ideas would have a foothold in the judiciary for the foreseeable future, and having such a strong progressive block on the Court looked like a positive development for Wilson and his policies. But a progressive-controlled Court also had its share of scandals.

For example, Holmes is often remembered for his infamous decision in the forced-sterilization case Buck v. Bell. The decision, which Brandeis joined in support, upheld the Commonwealth of Virginia’s right to forcibly sterilize a young woman, Carrie Buck, because she had a mental disability. In his decision, Holmes wrote, “Three generations of imbeciles is enough.”

The decision seems shocking to contemporary Americans, but forced sterilization and eugenics were viewed favorably by many progressives who agreed with Wilson’s theory of “social Darwinism” controlled by a strong government. Thomas Leonard explains the appeal of eugenics to early progressives: “The improvement of humankind, like any kind of breeding, could not be left to happenstance. It required scientific investigation and regulation of marriage, reproduction, immigration, and labor.”

While eugenics and forced sterilizations are extreme examples of progressive campaigns in the early 1900s, they offer a stark example of the core difference between the progressives’ vision for the country and the Founders’ vision. The Founders shaped the government to protect individual rights above all else. Progressives tried shaping the government to protect society as a collective whole—which at times required sacrificing individual rights (or individuals).

By the end of Wilson’s first term, America’s constitutionally limited government, bounded by the separation of federal powers, had a noticeable fourth branch welded onto it. Money, banking, international trade, and domestic business were now all regulated federally through the administrative state.

Historian Robert Higgs describes just how much the administrative state—along with America’s entrance into WWI—had changed government by the time Wilson left office: “The federal government expanded enormously in size, scope, and power. It virtually nationalized the ocean shipping industry. It did nationalize the railroad, telephone, domestic telegraph, and international telegraphic cable industries. It became deeply engaged in manipulating labor-management relations, securities sales, agricultural production and marketing, the distribution of coal and oil, international commerce, and markets for raw materials and manufactured products. Its Liberty Bond drives dominated the financial capital markets. It turned the newly created Federal Reserve System into a powerful engine of monetary inflation to help satisfy the government’s voracious appetite for money and credit. In view of the more than 5,000 mobilization agencies of various sorts—boards, committees, corporations, administrations—contemporaries who described the 1918 government as ‘war socialism’ were well justified.”

WOODROW WILSON’S academic writings reveal his ideals of creating a government-regulated utopia. While even his admirers are forced to admit that he fell far short of his utopia, his administration did succeed in sparking a quiet revolution in U.S. government.

The policies and laws Wilson enacted made the administrative state a permanent pillar of American government. His progressivism would lay the groundwork for the leviathan that today’s government has become, and his Supreme Court appointee Louis Brandeis (nick-named the “father of the New Deal”) would become one of the most influential Justices in history.

Wilson always thought of himself as the smartest guy in the room. And looking back at his legacy, maybe he was right. But smarts, and wisdom, are two very different things.