DR. AZADEH KHATIBI grew up in Tehran in the early 1980s. Her father wanted sons; he got two daughters. “He was like, ‘What is their future going to be like?’” she says. Iran’s new theocratic government oppressed women in every way, from clothing to schooling.

This was after the Islamic Revolution of 1979. The country’s constitution, written in 1906, had been thrown out; Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini became Supreme Leader. Women, who had freely worn dresses and socialized with men during the seventies, were suddenly forced to wear the hijab and banned from men’s spaces.

“At that point,” Dr. Khatibi remembers, “they’d closed the universities down for three years to revise the textbooks and make sure people were learning what was deemed ‘correct’ to learn. A lot of people’s lives got twisted in a really bad way.”

So the family left. Dr. Khatibi’s father wanted more for her than Iran would allow. They moved to Southern California, where women would not be treated as a separate class of citizens.

The only remedy to unequal freedom, Margaret Fuller said in 1845, “must come from individual character.”

‘The Great Lawsuit’

“HER FATHER WAS A MAN who cherished no sentimental reverence for woman, but a firm belief in the equality of the sexes… He addressed her not as a plaything but as a living mind.” That wasn’t written about Dr. Khatibi’s father, although perhaps it could have been. It’s from American journalist Margaret Fuller’s 1845 book Woman in the Nineteenth Century, about a character she based on herself. Fuller originally published the book as a serialized essay with a far-more-interesting title: “The Great Lawsuit: Man versus Men. Woman versus Women.”

“[M]an cannot, by right, lay even well-meant restrictions on woman,” Fuller wrote. What she asked for was simple: “We would have every arbitrary barrier thrown down,” she wrote. “We would have every path laid open to woman as freely as to man.”

For Fuller, each woman was an individual first and foremost. A woman’s femininity was a characteristic, not the essential whole of her. “What woman needs is not as a woman to act or rule, but as a nature to grow, as an intellect to discern, as a soul to live freely and unimpeded, to unfold such powers as were given her when we left our common home,” she wrote.

The only remedy to unequal freedom, she said, “must come from individual character.”

The vision Margaret Fuller laid out in 1845 is what draws immigrant families like the Khatibis to America. In the 179 years since Fuller’s book was published, America has rid itself of “every arbitrary barrier” legally preventing women from participating in government, industry, property-ownership, and art. In 1845 Fuller argued women could fill any office. “Let them be sea-captains, if you will,” she quipped. Today in America there is no field open to men that is not legally open to women. There are female captains at sea and female pilots in the sky.

But the oppressor-oppressed worldview still positions all women below men, regardless of individual circumstances, and maintains that women are an oppressed class that needs legal quotas, mandates, and set-asides to be truly empowered.

It’s a worldview belied by the success of women like Dr. Azadeh Khatibi, now a California ophthalmologist who is fighting mandatory “implicit bias” trainings in medical education.

Implicit Bias

“AZADEH” MEANS FREEDOM. It’s a fitting name for Dr. Khatibi.

Growing up in Southern California, she loved acting. She thought about studying to become an actress but wanted to feel like she was making a difference. “I thought, ‘I have to go to work every day and help someone,’” she says.

She also wanted security. Her early years in Iran affected her. “I grew up in this milieu of people in a constant state of shock and trauma and insecurity and worry,” she reflects.

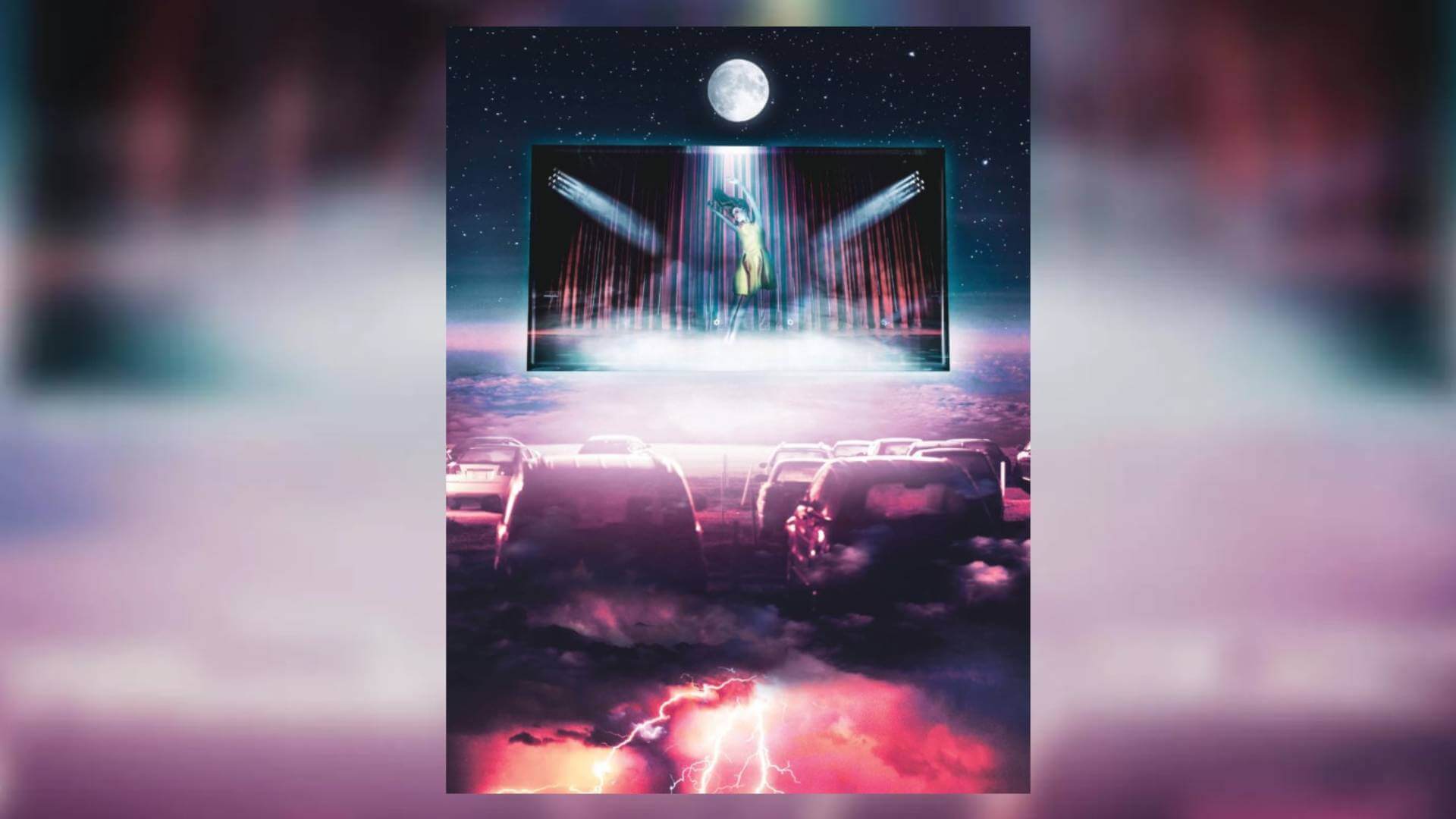

She studied ophthalmology at the University of California, Berkeley and did her residency at UC Irvine while raising two kids. She didn’t give up entirely on her Hollywood dreams: She produced several films over the past ten years, including the animated film Window Horses starring Sandra Oh.

Dr. Khatibi also taught continuing medical education (CME) courses, which doctors must take periodically to keep their licenses. But in 2019, California passed a new law requiring all CME courses to include implicit bias training.

Implicit bias training is designed to make people aware of how they might be stereotyping others based on sex, race, ethnicity, sexual orientation, or other characteristics. For doctors, the goal of implicit bias training is to prevent the unequal treatment of patients.

But there are a couple of problems: One, the jury’s out on whether implicit bias trainings have a positive impact, as Scientific American and MSNBC report. In fact, “[i]mplicit bias training can actually reinforce harmful stereotypes,” MSNBC notes. To paraphrase Chief Justice John Roberts, the way to stop discrimination is to stop discriminating. Implicit bias training encourages doctors to be ever-conscious of identity-based groups, which can undermine the goal of equal treatment for all.

The second problem is the state is forcing CME teachers like Dr. Khatibi to spend limited course-time on implicit bias training instead of allowing them to decide for themselves what’s relevant for doctors.

“You’re actually changing the narrative of medicine,” Dr. Khatibi says. “You are being forced by law to teach something else.” It reminded her of Iran. “When you grow up in a theocracy that’s very repressive, people are constantly worried about someone reporting them or doing the wrong thing,” she says. “It really messes up your psyche as an individual.”

There’s an awful irony in what California is doing: To help groups it believes are oppressed, including women and immigrants, the state is forcing an Iranian-born woman to teach bias trainings against her will.

Dr. Khatibi is represented by PLF in a lawsuit challenging the mandatory trainings.

Set-Asides and Quotas

THE GOVERNMENT’S TOP-DOWN MEDDLING can be frustrating for women who worked hard to rise in their industry.

Debbie Ferrari is, like Dr. Khatibi, a successful California professional. She spent almost 40 years moving up the ranks in the construction industry. She started in bookkeeping at a trucking company before moving to operations; now she’s a manager at the company.

Since the 1980s, California has set aside some public works contracts for minority- and women-owned businesses. The state’s “Construction Compliance Program” sets a goal of 15 percent minority-owned businesses and five percent women-owned businesses.

Ms. Ferrari works at a diverse company: They have truckers and staffers from Mexico, India, and Vietnam. “We’ve got a lot of women in our office,” Ms. Ferrari adds.

America’s history of legal oppression is a hard yoke to forget. But it should not determine how the law treats people in 2024.

But the company isn’t certified as minority- or woman-owned, so it can’t win certain public jobs. The sex and race of the company’s owners now “trump price and the ability to perform,” Ms. Ferrari says. The individual staffers at the company—including women like Ms. Ferrari—are being robbed of opportunities because of California’s artificial barriers.

Ms. Ferrari and the Californians for Equal Rights Foundation are represented by Pacific Legal Foundation in a lawsuit challenging the discriminatory set-asides.

A Victory in Iowa

IN JANUARY, PLF WON A VICTORY for equality in a separate lawsuit in Iowa: A federal judge ruled for PLF client Charles Hurley and struck down a gender quota for the State Judicial Nominating Commission. Iowa argued that the quota was “appropriately enacted to address the absolute absence of women” on the commission and that it remedied past discrimination. “Even if it would be appropriate to end the gender-balance requirement someday, today is not that day,” Iowa said.

But today is that day. In its decision, the court said it “cannot find the law is substantially related to any current discrimination.” The government bore the burden of showing its sex-based classifications passed strict intermediate scrutiny, and it failed that burden. The court ruled that Iowa’s quota violated the Equal Protection Clause of the Constitution.

It was a strike in the right direction—toward a government unfettered by identity-based obstacles.

The Future for Women

FOR A LONG TIME after the Founding, the American legal system failed women. Women could not participate in the political process. Married women couldn’t hold property in their own names.

The Fourteenth Amendment was ratified in 1868, guaranteeing all citizens “the equal protection of the laws.” Myra Bradwell, publisher of the Chicago Legal News, sued the State of Illinois the following year; she had passed the Illinois Bar exam but was denied a license because she was a married woman. Her case went before the Supreme Court in 1873.

She lost, 8 votes to 1. “The paramount destiny and mission of woman are to fulfill the noble and benign offices of wife and mother,” Justice Joseph Bradley wrote in a concurrence.

That history of legal oppression is a hard yoke to forget. But it should not determine how the law treats people in 2024. Obstacles of the past don’t justify obstacles now: What was right then is also right today.

American women are hardly a homogenous class. Even Dr. Khatibi and Ms. Ferrari, two successful California women with similar views, have vastly different experiences. Does it make sense to have a quota or mandate that lumps these two women, and all women, together as a group that needs government help?

The persistent worldview that all women in America are oppressed by male oppressors can, at times, venture into the absurd.

For instance: Last year country singer Luke Combs covered Tracy Chapman’s classic 1988 single, “Fast Car.” After Combs’ version hit No. 1 on the Billboard Country chart, The Washington Post published an article about how problematic the cover’s success was. Chapman, the Post argued, “as a black queer woman,” would “have zero chance” of having the same success as Combs, a white man.

Readers quickly disagreed, pointing out that Chapman’s original version was a big hit when released and that she was now earning royalties from Combs’ country version. The takeaway should be that art can be universal, one Twitter user argued. “That a black lesbian and a straight white man may feel the same depth and story despite identity differences. What if we pushed that narrative.”

In the leadup to the 2024 Grammys Awards in February, promos teased a performance by Luke Combs. But in a surprise at the ceremony, Tracy Chapman joined Combs for a moving duet of “Fast Car.”

“I had a feeling that I belonged,” the two sang together. “I had a feeling I could be someone.”

Afterwards, as the crowd cheered, Combs turned and bowed deeply to Chapman. He seemed visibly awed by her. It was a lovely moment between two successful stars—and no one watching could possibly come away thinking that Combs, by virtue of being a man, was the one with greater power. ♦