ON JUNE 12, 1967, the U.S. Supreme Court issued its landmark decision in the case of Loving v. Virginia, which ruled unanimously that state laws prohibiting interracial marriage violated the promise of equal protection before the law. That case became a famous touchstone of civil rights law, and was even the subject of a major Hollywood motion picture in 2016.

But a look at the contemporaneous media coverage of the case is telling, because it’s like entering a time machine to an era before every matter of public concern was hyper-politicized.

An article from The New York Times covering the Loving decision was brief and to the point. It recounts the facts of the case, quotes the decision written by then-Chief Justice Earl Warren, and provides brief explication of the case’s potential legal significance.

Here’s what the 1967 Times article doesn’t do: It doesn’t quote partisan activists on either side of the case who might have been invested in the outcome. It doesn’t note the party of the president who appointed Warren to the Court or characterize the Chief Justice’s ideological leanings. It doesn’t steer the reader’s response with loaded or emotional language. It’s little more than a dry, factual recounting of the Court’s decision.

As a constitutional lawyer, I’ll admit to feeling a little wistful about that bygone age when the courts could make even a historic decision and the media could report the event with simple, forthright clarity and equanimity. It’s a reminder that there was a time, in fairly recent memory, when the courts were seen as a reprieve from the hurly-burly of politics and partisanship.

Compare that sober response to today’s hysterically polarized climate, in which politics has seemingly infected everything. Where do we go for a reprieve from partisanship? Don’t let them fool you: it’s still the courts.

Courts are where individuals turn when politics has steeped too far into our lives. The Constitution (and by extension, the justices who enforce it) take some aspects of our lives off of the political table so that we can live our lives free of the backdoor deals, lobbying, cajoling, compromising, and unholy alliances that come with partisan politics.

At least that’s one view, and it’s the view that properly understands the role of the judiciary. An unfortunate competing view is that courts are merely another political branch, who should—and in practice, do—make political decisions rather than ones rooted in the Constitution.

This view manifests itself in the way many people now talk about the Supreme Court confirmation process. In Justice Amy Coney Barrett’s October 2020 confirmation hearings, politicians outright asked the nominee what she thought about global warming, abortion, systemic racism, COVID-19, and the Affordable Care Act—as if her personal political views are relevant to her capacity to judge. News reports now routinely report that “Republicans” have a 6-3 majority on the Court.” Some advocate court packing as a legitimate and necessary means of “balancing” the bench.

This creates a sort of self-fulfilling prophecy. In a recent speech, Justice Samuel Alito noted that after a group of politicians threatened to “restructure” the Court if it ruled on a Second Amendment challenge to New York law, the Court dismissed the case. He said that while the Court had made its decision independently, the fact that the politicians had made such a statement caused people to assume the Court was acting according to politics rather than according to principle.

It’s a mistake to think of the Court as an extension of the political sphere. The role of the judiciary is to enforce constitutional guarantees rather than acceding to political whim. Courts are supposed to be a bastion of liberty when the democratic process fails us.

When the Court has taken up its proper role of enforcing liberty against unwarranted violations, it’s been instrumental in many (if not most) of the biggest civil rights victories in United States history. The Loving case is one example, but there are several others: there’s Tinker v. Des Moines, which ruled that a school could not ban students from wearing black armbands to protest the war in Vietnam; and Gideon v. Wainwright, which ensured that states provide counsel for those too poor to afford representation in criminal cases; and NAACP v. Button, which denied Alabama’s attempt to collect the names of members of the NAACP and upheld the group’s First Amendment rights.

Cases like these transcend politics; in fact, they reject the idea that politics should be able to govern many aspects of our lives.

That’s not to say the courts have been perfect at protecting our constitutional rights. But where courts have done their worst, it’s often been exactly because they’ve abandoned constitutional guarantees of liberty in favor of some other guiding principle.

Fortunately, even when the Court has gotten it wrong, the arc of Supreme Court history has bended toward justice. Plessy v. Ferguson, which ruled that “separate is equal,” was followed by the Court’s landmark decision in Brown v. Board of Education. And Bradwell v. Illinois, which denied that women had a constitutional right to practice law, was followed by cases like U.S. v. Virginia, which affirmed equality of the sexes before law.

In the same vein, Kelo v. City of New London, which drastically expanded the government’s ability to take people’s property through eminent domain, will also be overturned. Decisions like The Slaughterhouse Cases and Williamson v. Lee Optical, which relegate the right to earn a living to second-class status, will be rectified.

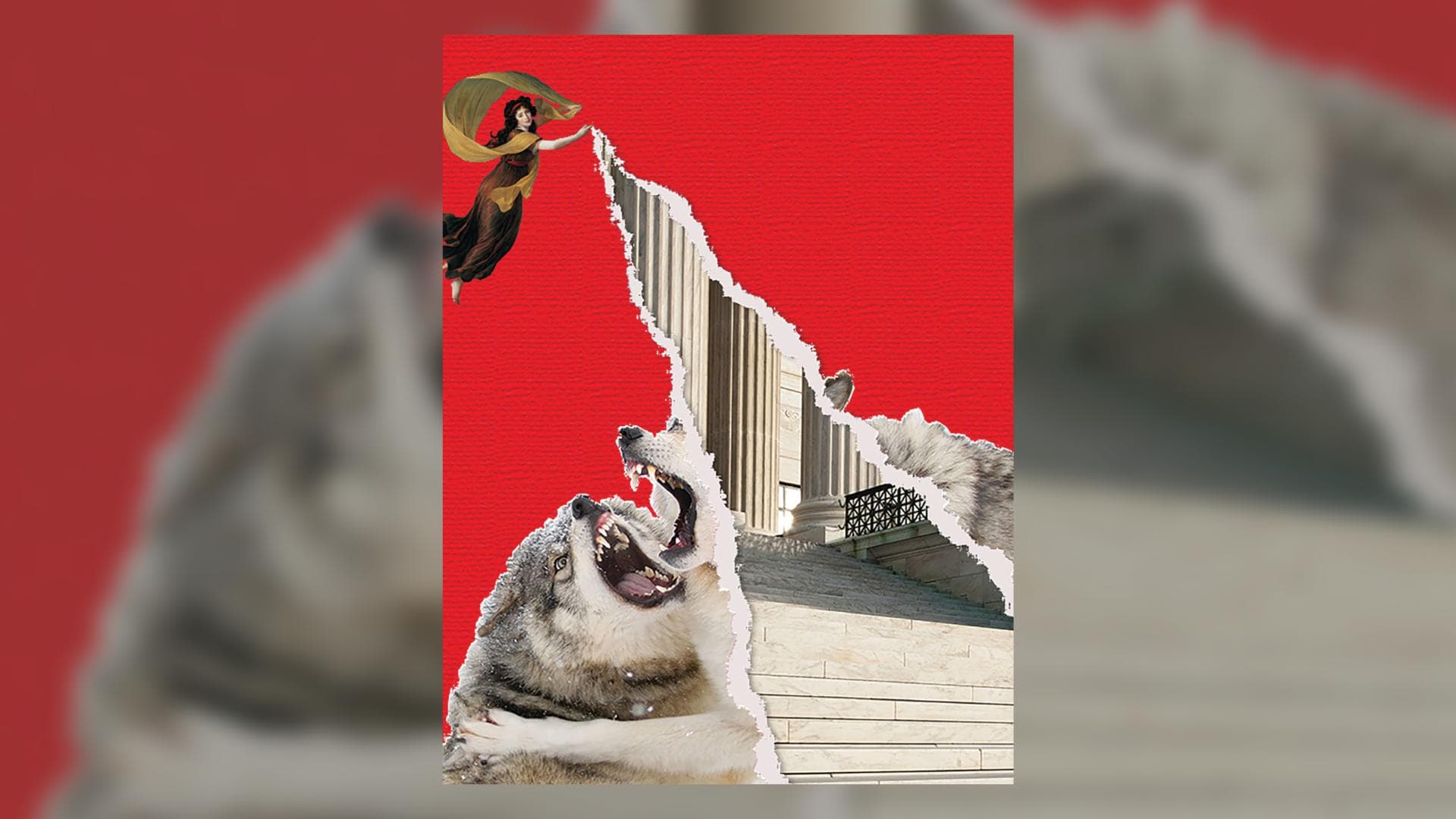

And that’s why we fight. Because we know that democracy is two wolves and a sheep voting on what’s for dinner, and we expect courts to be our refuge from those who would impose their political preferences rather than respect our constitutional rights. Courts ensure that the Constitution, and not majority rule, prevails. Courts put constitutional guarantees before politics.

We should embrace that more modest view of the courts’ role. Let’s resolve to step away from the heated, over-politicized focus on court decisions—in which every case is an existential threat—for a more measured response that focuses on the constitutional issues at stake. In the meanwhile, PLF will be fighting for liberty where it matters: in the last bastion for individual rights.